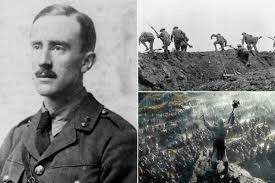

January 3, 1892 – September 2, 1973

Today marks the birthday of John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, born on January 3, 1892, in Bloemfontein, South Africa. While millions know him as the author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, fewer appreciate that Tolkien was first and foremost a medieval scholar—a Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford University whose deep knowledge of medieval literature, languages, and culture directly shaped the fantasy worlds that would capture the imagination of generations.

The Professor

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien held the prestigious position of Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford. He later became the Merton Professor of English Language and Literature, a post he held until his retirement in 1959. For thirty-four years, Tolkien taught Old and Middle English, Gothic, Old Norse, and medieval Welsh to Oxford students. His lectures on Beowulf were legendary—one former student, the poet W.H. Auden, wrote decades later that hearing Tolkien recite Beowulf was an “unforgettable experience,” adding that “the voice was the voice of Gandalf.”

Tolkien brought medieval texts to life for his students through dramatic recitation, treating them not as dusty academic exercises but as living poetry. He would recite passages in the original Anglo-Saxon, his voice filling lecture halls with the ancient rhythms and alliterations of a language most students found impenetrable on the page. One student remembered how Tolkien “could turn a lecture room into a mead hall,” making his audience feel they were listening to an Anglo-Saxon scop (poet) performing for warriors and kings.

“Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”

In November 1936, Tolkien delivered what would become one of the most influential lectures in literary history: “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics.” Before Tolkien’s intervention, scholars had largely treated Beowulf as a historical document valuable primarily for what it revealed about Anglo-Saxon society, dismissing its monsters and dragons as primitive distractions from the “real” historical content.

Tolkien revolutionized this view. He argued that the poem’s monsters—Grendel, Grendel’s mother, and the dragon—were not flaws but central to the work’s meaning and power. The poem, he insisted, should be read as literature, as poetry, not merely mined for historical facts. His lecture transformed Beowulf studies and helped establish the poem’s place in the literary canon. Even today, it remains required reading for anyone seriously studying Old English literature.

This scholarly work was not separate from Tolkien’s creative writing—it was inextricably linked. The themes, structures, and even specific details of Beowulf would profoundly influence both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien had completed a full translation of Beowulf by 1926, though characteristically, he never published it during his lifetime. His son Christopher finally brought it to print in 2014, giving readers access to Tolkien’s interpretation of the poem he loved best.

The Languages Came First

What many readers of Tolkien’s fiction don’t realize is that Middle-earth emerged from his linguistic creations, not the other way around. Tolkien was a philologist—a scholar of languages—and he had a peculiar hobby: inventing languages for pleasure. He began creating his own languages as a teenager, developing complex grammar rules, sound systems, and vocabulary.

As he later wrote in a letter, he felt these languages needed “a habitation”—a world and a history to give them context and meaning. Middle-earth was built to house his invented Elvish tongues, Quenya and Sindarin. The stories of The Silmarillion, The Hobbit, and The Lord of the Rings grew organically from his desire to create a mythology for his languages, much as the myths and legends of the ancient world provided context for Greek, Latin, or Old Norse.

This linguistic foundation is why Tolkien’s world-building feels so extraordinarily deep and authentic. He wasn’t just making up fantasy names; he was constructing languages with internal consistency and historical development, then creating the cultures, histories, and geographies that would naturally produce those languages. When Tolkien writes that the Elvish word for “friend” is mellon, he’s drawing from a fully developed linguistic system with roots, sound changes, and grammatical structures.

Medieval Sources and Inspirations

Tolkien’s fiction is steeped in medieval literature and culture. The list of medieval texts that influenced his work is extensive:

Beowulf provided the template for The Hobbit‘s dragon Smaug (whose name comes from the Old Norse word smugan, meaning “to squeeze through a hole”), the idea of a hero facing monsters, and the elegiac tone of heroes fighting against inevitable doom. The barrow-wights in The Lord of the Rings echo the undead creatures of Norse sagas, while the Riders of Rohan speak a language modeled on the Old English of Mercia, where Tolkien grew up.

The Völsunga Saga and other Norse sagas influenced the story of the cursed ring, the concept of fate and doom, and the tragic heroism that pervades Tolkien’s work. The character of Gandalf takes his name directly from a dwarf in the Norse Poetic Edda, as do the names of Thorin’s company in The Hobbit.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, which Tolkien edited and translated with E.V. Gordon, influenced his depiction of courtesy, honor, and the relationship between civilization and the wild. The medieval poem Pearl shaped his understanding of loss, longing, and the nature of paradise.

Medieval Christian theology and philosophy deeply informed Tolkien’s moral universe, with its emphasis on mercy, grace, the corruption of power, and the eucatastrophe (his term for the sudden turn from tragedy to joy, drawn from Christian salvation theology).

Even his elves are rooted in medieval tradition. Tolkien transformed the diminutive, mischievous elves of English folklore into noble, immortal beings more akin to the álfar of Norse mythology—powerful, beautiful, and fundamentally other than human.

The Inklings and Oxford

Tolkien’s academic life at Oxford brought him into a circle of remarkable friends, most notably C.S. Lewis. The two men met in 1926 while discussing faculty politics, and despite initially disliking each other, they became close friends. Both were members of the Inklings, an informal literary group that met in Lewis’s rooms at Magdalen College and at the Eagle and Child pub (known to members as “The Bird and Baby”).

The Inklings read their works-in-progress aloud to each other for feedback and discussion. Tolkien read chapters of The Lord of the Rings to the group as he wrote them, receiving encouragement and criticism from Lewis and the others. These meetings provided Tolkien with an audience of fellow scholars and writers who could appreciate both the linguistic complexity and the literary ambition of his work.

Tolkien’s famous essay “On Fairy-Stories,” delivered as the 1939 Andrew Lang Lecture at the University of St. Andrews, emerged from conversations within this circle. In it, he defended fairy tales and fantasy as serious literature capable of profound truth, arguing that such stories offer “recovery, escape, and consolation”—recovery of a clear view of the world, escape from the prison of mundane reality, and consolation through the possibility of joy.

The Tension Between Scholar and Storyteller

Tolkien’s dual career as medieval scholar and fantasy writer created tensions. Some of his academic colleagues felt he wasted his scholarly talents on fiction, believing that if he had devoted all his energies to academic publishing, he would have produced groundbreaking scholarly works. Others accused him of neglecting his scholarly responsibilities in favor of his creative writing.

The truth is more complex. Tolkien did produce significant scholarly work—his Beowulf lecture alone has influenced generations of scholars. He edited medieval texts, translated ancient poems, and contributed to the Oxford English Dictionary (working on words beginning with ‘W,’ including “walrus,” over which he reportedly struggled mightily). His academic publications were relatively few, but they were profoundly influential.

At the same time, Tolkien himself sometimes felt torn. He spent decades working on The Silmarillion, attempting to create a complete mythology for Middle-earth, but his perfectionism and his academic training made him reluctant to publish work he considered incomplete. The result was that much of his creative work remained unpublished at his death, leaving his son Christopher to edit and publish The Silmarillion (1977) and the twelve-volume History of Middle-earth series (1983-1996).

Perhaps the fairest assessment is that Tolkien’s scholarship and his fiction were not in competition but were two expressions of the same deep engagement with medieval literature and language. His fiction communicated medieval themes, values, and aesthetics to millions who would never read Beowulf or the Völsunga Saga in the original. In this sense, he may have done more to keep medieval literature alive in popular consciousness than any amount of scholarly articles could have achieved.

A Legacy for the Ages

When The Hobbit was published in 1937, it was an immediate success. The Lord of the Rings, published in three volumes between 1954 and 1955, had a slower start but eventually became a cultural phenomenon, particularly in the 1960s when it found an enthusiastic audience among young people. By the time of Tolkien’s death in 1973, he had transformed the fantasy genre and inspired countless writers to create their own imagined worlds.

Today, through Peter Jackson’s film adaptations and the recent Rings of Power series, Tolkien’s work continues to reach new audiences. But at the heart of all this spectacular popular success is the work of a quiet Oxford professor who loved medieval languages and literature with such passion that he devoted his life to both studying and recreating their magic.

The Birthday Toast

Fans around the world honor Tolkien’s birthday with a simple tradition: at 9 PM local time, they raise a glass and say, “The Professor!” It’s a fitting tribute—a recognition that the man who gave us hobbits, elves, dwarves, and dragons was, first and foremost, a teacher and scholar who believed that medieval literature had something vital to say to the modern world.

So tonight, whether you’re reading The Lord of the Rings for the first or the fiftieth time, whether you’re studying Beowulf in the original or simply remembering the wonder you felt when you first discovered Middle-earth, raise a glass to J.R.R. Tolkien.

The Professor!

What’s your favorite Tolkien work, and how did you first discover Middle-earth? Share your memories in the comments!

For more on the medieval sources and historical context behind Tolkien’s work, look out for my new book The History Behind Lord of the Rings, coming later this year!

Leave a comment